It is well established that Americans are falling short of key nutrients, and research shows that low-income and food-insecure Americans are at greater risk for essential nutrient shortfalls. Dietary supplements, like the multivitamin/mineral, provide shortfall nutrients and have been shown to help fill nutrient gaps. Increasing access to dietary supplements may help low-income and food-insecure individuals meet their nutritional needs.

Under-consumption of calcium, potassium, dietary fiber,

and vitamin D is of public health concern for the general population.

Nutrient shortfalls

Getting all essential nutrients from the diet is preferred, but data show that most Americans fall short in many key nutrients.1 In fact, the Food and Drug Administration and the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) identified that under-consumption of calcium, potassium, dietary fiber, and vitamin D is of public health concern for the general U.S. population because low intakes are associated with particular health concerns.2 Iron was also identified to be of public health concern in adolescent girls and women of reproductive age, as well as in breastfed infants ages 6 through 11 months.3,4 In pregnant women, under-consumption of folic acid (in the first trimester), iron, and iodine is also of public health concern.5,6 Additionally, the current DGAs indicate that adolescent females have low dietary intakes of protein, folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, choline, and magnesium, and that dietary protein and vitamin B12 are more likely to be under-consumed in older adults (60 and older).

Under-consumption of iron is of public health concern for

adolescent girls, women of reproductive age,

and breastfed infants 6–11 months.

Under-consumption of folic acid, iron, and iodine

is of public health concern for pregnant women.

Nutrient shortfalls are more prevalent in Americans from low-income and food insecure households

Low-income households

Research using government data shows that low-income Americans are at greater risk for essential nutrient shortfalls than Americans from higher-income households. In a study conducted to examine shortfall nutrient intakes by poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), men and women in the lowest PIR category had significantly lower micronutrient intakes compared to those in the highest PIR category.7

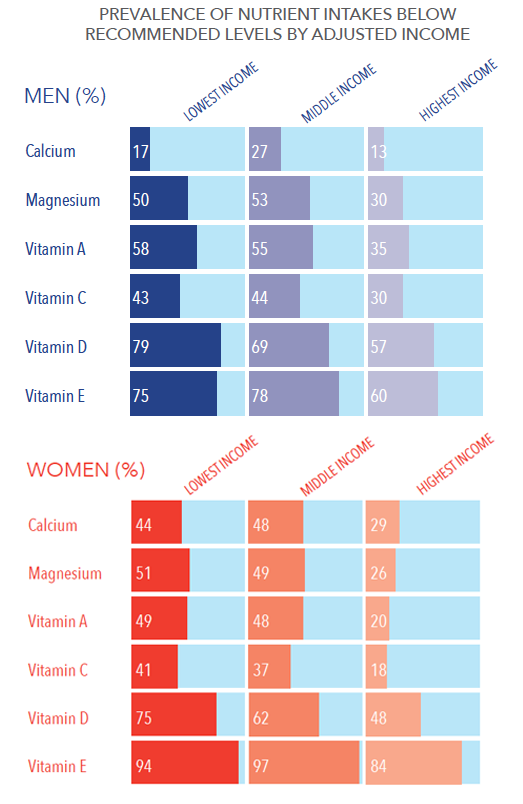

Further, adults at the lowest adjusted household income had a significantly higher prevalence of inadequate nutrient intakes (calcium, magnesium, and vitamins A, C, D, and E) compared to those at the highest adjusted income.8 The percentage of men and women who had inadequate intakes of these shortfall nutrients was also significantly higher in the middle PIR category compared to the highest PIR category, showing that micronutrient inadequacy is widespread in adults with lower incomes.

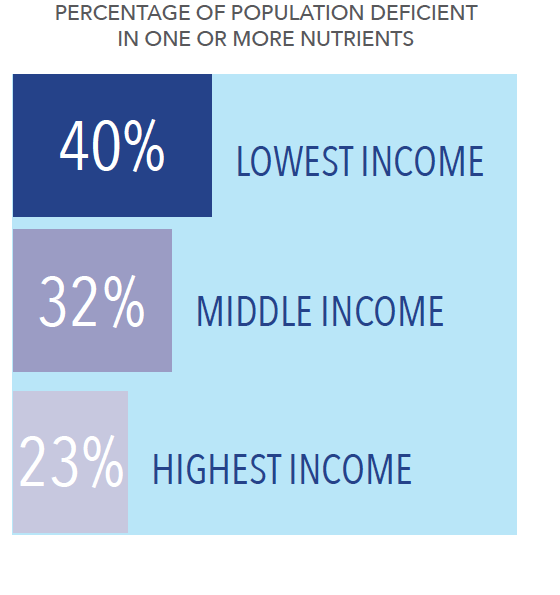

These results are reinforced by a study in which biological measures of nutrient status were compared across household income categories.9 Individuals from low PIR households were more likely to be at risk of micronutrient deficiency or anemia (indicative of vitamin B6, vitamin B12, or iron deficiency) than those from higher household income categories. Forty percent of individuals from low- income households were deficient in one or more micronutrients (vitamins B6, B12, C, and/or D) and/or anemic, compared to 32% and 23% of individuals from medium- and high-income households, respectively.

Inadequate nutrient intakes are of particular concern in women of childbearing age because a mother’s nutrition before and during pregnancy, as well as during breastfeeding, impacts the baby’s health. Results of a study show that mean intakes of several shortfall nutrients, including potassium, calcium, magnesium, and iron, were significantly lower in women of childbearing age living in low-income households compared to those in high-income households.10

In adults over 65 years of age, national data show that diet quality tends to be poorer in those with low-income levels.11 Poor dietary quality is associated with chronic disease, frailty, and death for older adults.12, 13, 14

Food-insecure households

Research also indicates that adults living in food-insecure households have a higher risk of micronutrient inadequacy than food-secure adults. In a recent study, the prevalence of risk of inadequacy was higher in both men and women from food-insecure households for magnesium, potassium, vitamins A, B6, B12, C, D, E, and K.15 Food-insecure men also had a higher risk of inadequate selenium, and zinc intakes relative to their food-secure counterparts. In addition, food insecurity is associated with lower diet quality in older adults.16

In children, when considering nutrient intakes from food alone, food-insecure girls and boys were at higher risk of inadequate intakes for vitamin E, calcium, and magnesium compared to food-secure girls and boys, and food-insecure girls were also at higher risk of inadequate intakes for vitamins A and D.17 In terms of total intake (food and dietary supplements), girls and boys from food-insecure households were at higher risk for inadequate intakes of vitamin D and magnesium, and girls also had higher risk for inadequate calcium intakes compared with those from food-secure households. Food-insecure adolescent girls (ages 14 – 18 years) were at higher risk of micronutrient inadequacies than other age and gender groups.

Dietary supplements can help fill nutrient gaps

Research suggests that dietary supplements help to reduce the proportion of the U.S. population at risk for inadequate intakes of several micronutrients including vitamin C, vitamin D, and calcium.18 Additionally, for some nutrients including vitamins B6, B12, C, and D, dietary supplements provide a greater contribution to overall intake compared to intake from food. 19 ,20, 21 When considering nutrient intake using the Total Nutrient Index (TNI), which reflects total usual intakes of eight underconsumed micronutrients identified by the DGAs (vitamins A, C, D, and E, and calcium, magnesium, potassium, and choline), recent research shows that nutrient intake is significantly higher in adult dietary supplement users compared to non-users.22 Additionally, TNI scores are significantly higher in those living with food security versus food insecurity.

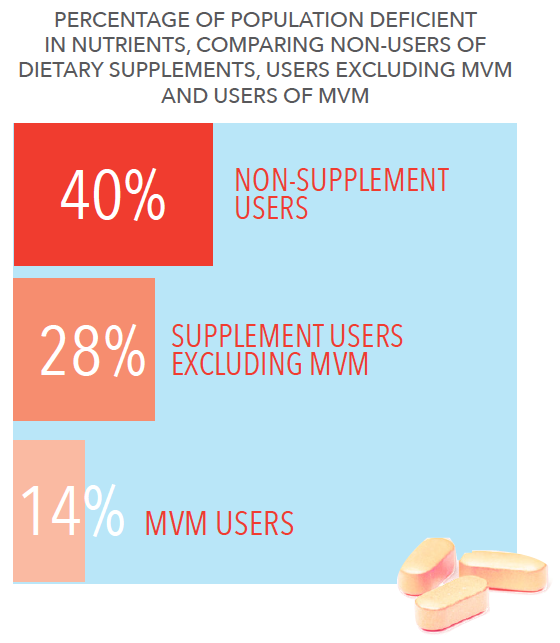

Research specifically demonstrates that users of multivitamin/minerals (MVMs) have a lower risk of vitamin deficiency or anemia than those who do not take dietary supplements.23 Forty percent of individuals identified as non-users of dietary supplements were shown to be deficient in one or more vitamins and/or anemic, compared to 28% of users of other dietary supplements and only 14% of MVM users.24 MVM use is associated with a lower prevalence of inadequate nutrient intakes and decreased risk of nutrient deficiencies, with a more dramatic impact seen in those who take MVM frequently.25

A recent study suggests that pregnant women in the U.S. do not meet recommendations for key essential nutrients, and that dietary supplements reduce the risk of inadequacy.27 Many of these women did not meet the Estimated Average Requirement for key nutrients, including vitamins A, C, D, E, K, B6, folate, choline, iron, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and zinc. Nutrient supplements were consumed by approximately 69% of women who were pregnant, which reduced the prevalence of those at risk for inadequate intakes of these nutrients but also increased the risk of excessive iron and folic acid intakes.

In a recent study, the risk of nutrient inadequacy was lower in adults living in food-secure households, and dietary supplements contributed a larger proportion to nutrient intake among adults living in food-secure households compared to those living in food-insecure households. Children from food-insecure households are less likely to take dietary supplements compared to food-secure children.27 The potential consequences of this are evident in new research showing that food-insecure children were at greater risk of inadequate vitamin D intake than food-secure children when comparing food intake alone, but the magnitude of this difference by food security status increased when intake from both food and dietary supplements was considered.28 Vitamin D intake in childhood plays a role in the development of peak bone mass, which is important for the prevention of fractures throughout the lifespan.29

1 The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): USDA, Agricultural Research Service; 2020.

2 U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

3 The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): USDA, Agricultural Research Service; 2020.

4 U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

5 The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Washington (DC): USDA, Agricultural Research Service; 2020.

6 U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

7 Bailey RL, Akabas SR, Paxson EE, Thuppal SV, Saklani S, Tucker KL. Total Usual Intake of Shortfall Nutrients Varies With Poverty Among US Adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):639-646.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.11.008

8 Bailey RL, Akabas SR, Paxson EE, Thuppal SV, Saklani S, Tucker KL. Total Usual Intake of Shortfall Nutrients Varies With Poverty Among US Adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):639-646.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.11.008

9 Bird JK, Murphy RA, Ciappio ED, McBurney MI. Risk of Deficiency in Multiple Concurrent Micronutrients in Children and Adults in the United States. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):655. Published 2017 Jun 24. doi:10.3390/nu9070655

10 Storey ML, Anderson PA. Vegetable Consumption and Selected Nutrient Intakes of Women of Childbearing Age. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(10):691-696.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.07.014

11 Long T, Zhang K, Chen Y, Wu C. Trends in Diet Quality Among Older US Adults From 2001 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e221880. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1880

12 Nowson CA, Service C, Appleton J, Grieger JA. The Impact of Dietary Factors on Indices of Chronic Disease in Older People: A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(2):282-296. doi:10.1007/s12603-017-0920-5

13 Bollwein J, Diekmann R, Kaiser MJ, et al. Dietary quality is related to frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(4):483-489. doi:10.1093/gerona/gls204

14 Haveman-Nies A, de Groot L, Burema J, et al. Dietary quality and lifestyle factors in relation to 10-year mortality in older Europeans: the SENECA study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(10):962-968. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf144

15 Cowan AE, Jun S, Tooze JA, et al. Total Usual Micronutrient Intakes Compared to the Dietary Reference Intakes among U.S. Adults by Food Security Status. Nutrients. 2019;12(1):38. Published 2019 Dec 22. doi:10.3390/nu12010038

16 Leung, CW and Wolfson, JA. Food Insecurity Among Older Adults: 10-Year National Trends and Associations with Diet Quality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021; 69: 964-971. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16971

17 Jun S, Cowan AE, Dodd KW, et al. Association of food insecurity with dietary intakes and nutritional biomarkers among US children, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(3):1059-1069. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab113

18 Cowan AE, Jun S, Tooze JA, et al. Total Usual Micronutrient Intakes Compared to the Dietary Reference Intakes among U.S. Adults by Food Security Status. Nutrients. 2019;12(1):38. Published 2019 Dec 22. doi:10.3390/nu12010038

19 Bailey RL, Akabas SR, Paxson EE, Thuppal SV, Saklani S, Tucker KL. Total Usual Intake of Shortfall Nutrients Varies With Poverty Among US Adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):639-646.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.11.008

20 Fulgoni VL 3rd, Keast DR, Bailey RL, Dwyer J. Foods, fortificants, and supplements: Where do Americans get their nutrients?. J Nutr. 2011;141(10):1847-1854. doi:10.3945/jn.111.142257

21 Cowan AE, Jun S, Tooze JA, et al. Total Usual Micronutrient Intakes Compared to the Dietary Reference Intakes among U.S. Adults by Food Security Status. Nutrients. 2019;12(1):38. Published 2019 Dec 22. doi:10.3390/nu12010038

22 Cowan AE, Bailey RL, et al. Total Nutrient Index is a Useful Measure for Assessing Total Micronutrient Exposures Among US Adults. The Journal of Nutrition.2022;152(3)863-871. doi:10.1093/jn/nxab428

23 Bird JK, Murphy RA, Ciappio ED, McBurney MI. Risk of Deficiency in Multiple Concurrent Micronutrients in Children and Adults in the United States. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):655. Published 2017 Jun 24. doi:10.3390/nu9070655

24 Bird JK, Murphy RA, Ciappio ED, McBurney MI. Risk of Deficiency in Multiple Concurrent Micronutrients in Children and Adults in the United States. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):655. Published 2017 Jun 24. doi:10.3390/nu9070655

25 Blumberg JB, Frei BB, Fulgoni VL, Weaver CM, Zeisel SH. Impact of Frequency of Multi-Vitamin/Multi-Mineral Supplement Intake on Nutritional Adequacy and Nutrient Deficiencies in U.S. Adults. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):849. Published 2017 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/nu9080849

26 Bailey RL, Pac SG, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Reidy KC, Catalano PM. Estimation of Total Usual Dietary Intakes of Pregnant Women in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195967. Published 2019 Jun 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5967

27 Jun S, Cowan AE, Tooze JA, et al. Dietary Supplement Use among U.S. Children by Family Income, Food Security Level, and Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Status in 2011⁻2014. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1212. Published 2018 Sep 1. doi:10.3390/nu10091212

28 Jun S, Cowan AE, Dodd KW, et al. Association of food insecurity with dietary intakes and nutritional biomarkers among US children, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(3):1059-1069. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab113

29 Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, et al. The National Osteoporosis Foundation's position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations [published correction appears in Osteoporos Int. 2016 Apr;27(4):1387]. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(4):1281-1386. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3440-3